The beautiful world of random numbers

All of us encountered chance in one way or another. That guilty moment when guessing in a multiple-choice exam, that heart-throbbing suspense when hoping that you draw your crush’s name in the class Christmas exchange gift, that spin the bottle game of truth or dare when drinking with friends, or even that simple coin toss whether to eat out or not. Chance is entangled to our lives but ironically, most of us find it hard to grasp or understand [1].

First time students of statistics and even novice teachers admit that statistics is a difficult field of study as it go against common intuition [2]. In real life situations, most people feel uncomfortable when confronted with the concept of randomness. There is this tendency to believe that things happen for a reason and that there must be an explanation for the present state of things. These sentiments can be traced back to the earliest writings and theological teachings of almost all civilizations [3].

Operational mathematics, in its manner and form, is largely based from the axioms, theorems and propositions of the ancient Greeks. They did not pioneer rigid mathematical treatment of the theory of randomness because; First, they believe that the future is governed by the will of gods. Second, they believe on absolute truth proved by logical assumptions. And third, their number system is impractical for calculations with fractions and non-positive numbers. These would imply that probabilities and chance would be irrelevant and an impossibility for them [4].

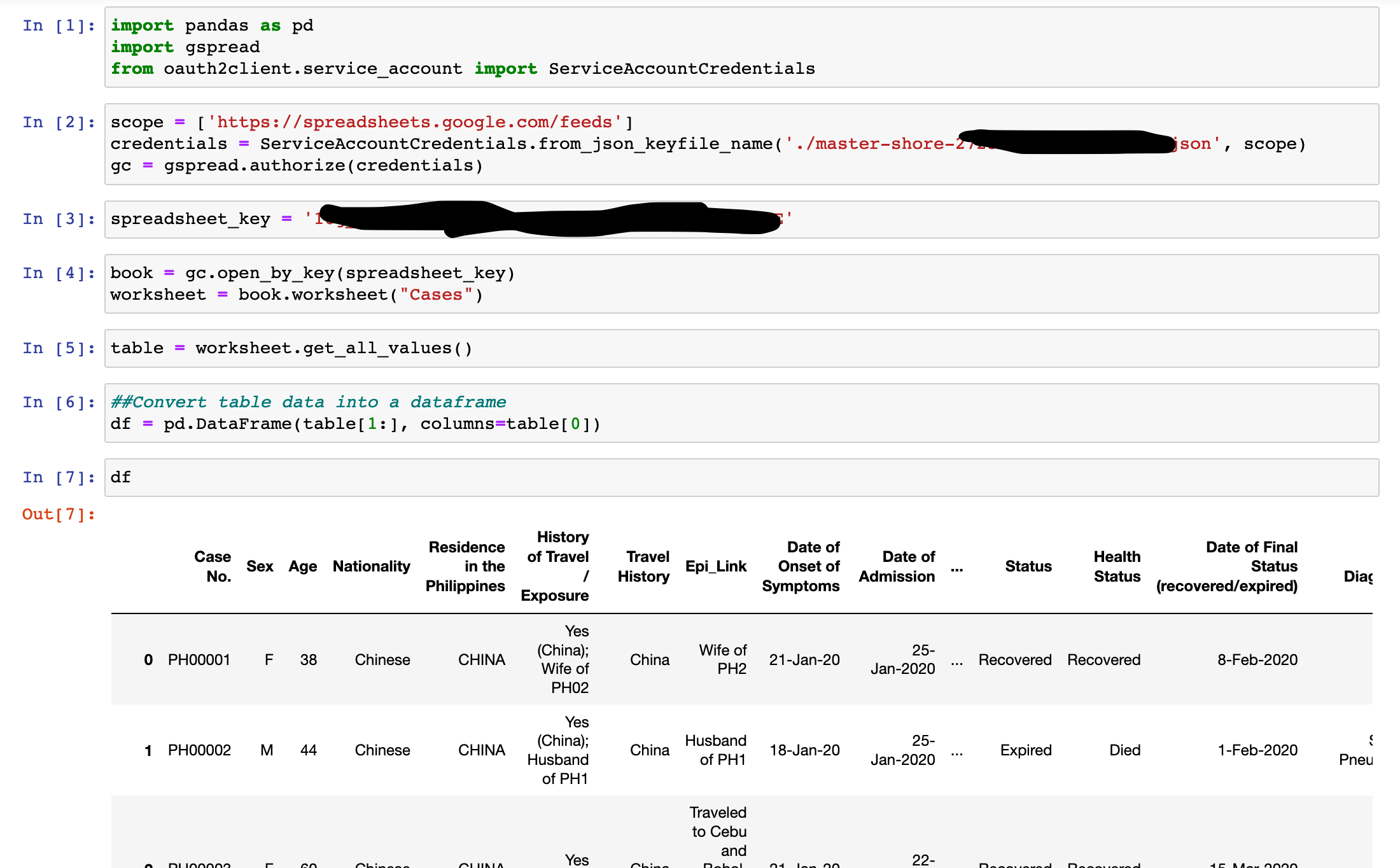

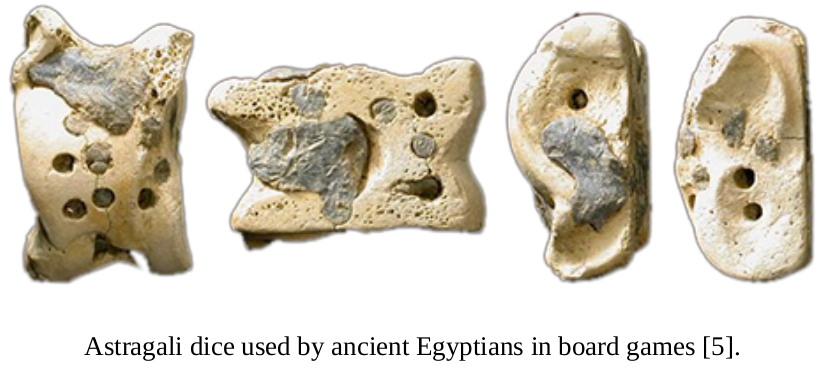

The first advancement in the theory of randomness came much later when a medical doctor turned gambler Gerolamo Cardano wrote a book titled ‘Book on the Games of Chance’ that depicts strategies in playing card games, backgammon, and a primitive dice called the astragali [4]. This work by Cardano became the basis of the works of Galileo Galilei (equiprobability of tossing three dice), Blaise Pascal (fundamental counting theory and concept of mathematical expectation) and Jacob Bernoulli (law of large numbers) [1].

Another notable contribution to the theory if randomness was from an Englishman shopkeeper by the name of John Graunt. In his book ‘Natural and Political Observations Made Upon The Bills of Mortality’, he was able to predict accurately the mortality rates of London in a ‘normal’ year and also the number of casualties of a particular disease or incident [3].

From these insights in gambling and population dynamics, started our ‘confidence’ that even randomness follows certain rules. The theory of randomness peaked interest and became central in the study of thermodynamics and quantum theory.

At the time, early scientists used draw balls from a ‘well-stirred’ urn for their random numbers. Eventually, tables of random numbers generated from census reports where published but where deemed inadequate for large sampling experiments [6]. Over the years, much of the development was focused on producing large scale random numbers and at a faster rate through deterministic mathematical algorithms.

Humanity has been using random numbers since antiquity. In ancient Egypt, chance have been used to divide property, delegate civic responsibilities or privileges, settle disputes among neighbors, device strategies in battle, and drive the play in games [1]. Often they use randomness to ensure fairness, to prevent dissension, and to acquire divine direction.

Modern times have changed a lot, and random numbers are becoming more essential to most of our technologies. Many areas in physics require simulations of natural phenomena and physical systems. For a more realistic rendering, random numbers are often needed. In the field of statistics, random sampling is often necessary to obtain a generalization of the population.

Exhaustive numerical problems often require large amount of random numbers to crunch and brute force all possible solutions. One of such application is the Monte Carlo method which consists of simulation techniques that uses large amount of random numbers [7]. This method has vast applications in calculating definite integrals, systems of equations or mathematical models in higher dimensions.

Current high-definition movies and video games rely mostly on the realistic rendering of characters and scenes. Random numbers are often used to identify parameter values in which the rendering will fit observations in natural systems. One example is the Disney movie ‘Frozen’. The producers based the simulations of the snow dynamics on a hybrid Eulerian/Lagrangian Material Point Method in which simulation parameters like the number of snow particles in a grid were chosen at random.

Complex systems in economics, sociology, and politics often need strategic analysis for decision making. These systems and their analysis can be understood better by using ‘game theory’. Game theory is a congregate of models where a game is any competitive activity in which players contend with each other according to a set of rules [8]. Examples include political candidates vying for votes, court judges deciding on a case, animals fighting for a prey etc. Random numbers are central to the simulations involved in game theory for it is necessary to exhaust all possible outcomes in a game and optimize the decision process.

Computer algorithms often require random numbers to test its robustness. Of particular interest is its application in cryptography which aims to ensure the integrity and security of data. Branching to the applications of cryptography, modern ideas on innovating monetary and banking systems are starting to take place. Cryptocurrency has become of particular interest for the decentralization of banks and other financial institutions. The process involves person to person transactions which are recorded via a public ledger monitored by individuals called ‘miners’ [9]. As a result transaction fees and product prices becomes lower and since the currency transcends national boundaries, it can be used everywhere. Of particular interest to the implementation of cryptocurrencies would include environmental and sustainability factors as there will be a reduction of our need of paper bills and metallic coins.

For a start, there is no such thing as a random number [6]. Rather we think of random numbers as a ‘sequence’ and not just a single number. Whether a number belongs to a random sequence is entirely dependent to the previous and the next numbers. Generating random numbers is no easy task [10]. Generally, random number generators are classified based on how they are generated. The types include, Pseudo Random Number Generators (PRNGs), Cryptographically Secure Random Number Generators (CSRNGs) and True Random Number Generators (TRNGs).

If the random number generator looks random and passes many standardized statistical tests of randomness, then it can be classified as a PRNG. This type of generator rely on mathematical algorithms to generate random numbers. The numbers produced possess the same statistical properties of ‘real’ random numbers. PRNGs are characterized by being deterministic as they are governed by a particular function. PRNGs are also periodic since they use bounded memories. Applications that uses PRNGs almost always require algorithms that produces random numbers of long periods. Some even uses \(2^{256}\) or higher [11]. PRNGs are useful for simulations but definitely not for cryptographic applications [12].

If a random number generator produces random numbers that looks random and is unpredictable, then it is classified a CSRNG. Basically, it is like the PRNGs that use deterministic algorithm to generate numbers but does not leak any information about the next number [11]. Examples include the CSPRNGs of Unix-based operating systems (OS) called block devices: /dev/random and /dev/urandom. These two are system files where the operating system pools random OS-dependent events such as system clock, elapsed time between keystrokes or mouse movement, and other physical noise sources [10].

Two operations are used in seeding these CSRNGs. In /dev/random, the operation is called ‘blocking’, where the process blocks an application until sufficient entropy is reached. Entropy in this system is defined as the random bits stored in a file. The pool of bits in this file is called entropy pool and are extracted from physical processes available to the software like mouse movements and keyboard inputs. On the other hand, /dev/urandom makes work whatever is available in the OS’s entropy pool without blocking [13].

The last type of random number generators is the TRNG which looks random, is unpredictable and cannot be reliably reproduced. These type of generators are mainly based from the digitization of physical processes. Such physical processes and sources include: (1) elapsed time between emissions of particles during radioactive decay; (2) thermal noise from semiconductor diode or resistor; (3) the frequency instability of a free running oscillator; (4) the amount a metal insulator semiconductor capacitor is charged during a fixed period of time; (5) air turbulence within a sealed disk drive which causes random fluctuations in disk drive sector read latency times; and; (6) sound from a microphone or video input from a camera.

Generally, TRNGs are the best generators for applications in security and encryptions as they are non-deterministic [12]. One point of concern with TRNGs is that they are inherently biased. These biases are due to our inability to device balanced physical processes. These biases can be removed by using post-processing algorithms that balance out the bits.

There are also free services on the web that offer a finite sequences of random numbers. One particular and useful website is random.org that obtains their data from atmospheric noise [14] and HotBits that uses the radioactive decay of Cesium atoms [15].

Random numbers generated from physical processes are vital our current mode of communication that relies on the transmission of data through computer systems and networks. Our daily activities like sending emails, browsing social media, online banking and shopping depend on these telecommunication platforms and the world wide web secured by random numbers.

Want to collaborate? Message me in LinkedIn.

References:

[1] D. Bennett. Randomness. 1998. Harvard University Press.

[2] J. Piaget and B. Inhelder. The Origin of the Idea of Chance in Children. 1975. W. W. Norton

[3] G. Markowsky. The Sad History of Random Bits. Journal of Cyber Security. 2014. River Publishers

[4] L. Mlodinow. The Drunkard’s Walk: How Randomness Rules Our Lives. 2008. Pantheon

[5] J. D. Norton. Dice

[6] D.E. Knuth. Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms. 1968. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Inc.

[7] J. Gentle. Random Number Generation and Monte Carlo Methods. 2002. Springer-Verlag New York

[8] M. J. Osborne. An Introduction to Game Theory. 2003. Oxford University Press

[9] Bitcoin bitcoin.org

[10] A. Menezes P. van Oorschot and S. Vanstone. Handbook of Applied Cryptography. 1997. CRC Press

[11] B. Schneier. Applied Cryptography, Second Edition: Protocols, Algorthms, and Source Code in C. 1994. Wiley

[12] A. McAndrew. Introduction to Cryptography with Open-Source Software. 2011. CRC Press

[13] M. Sheth.Cryptographically Secure Pseudo-Random Number Generator (CSPRNG)

[14] random.org

[15] J. Walker. HotBits: Genuine random numbers, generated by radioactive decay